Mobile video games have always been underappreciated and considered to be a step down when it comes to electronic entertainment for conservative reasons. It goes without saying that this is nothing new. Nokia introduced the now-iconic Snake game on their 6610 cell phone model back in 1997. This classic title entertained kids from all over the world in the late 90s thanks to a mechanic that had already been devised 20 years earlier, with the original Blockade arcade game developed by Gremlin.

Maybe it’s that feeling of intrusiveness in the industry that’s deemed cell phones as intruders in a business that’s not their own, leaving them without the recognition they deserve after more than two decades of constant evolution and a handful of milestones that the rest of the industry would have loved to see. And what’s worse, leaving aside the preservation work that, as we’re now seeing, is more necessary than ever, given the obsolescence of software distribution systems in non-physical format.

If we forget for a minute about the minigames included in the ancient PDAs, it can be said that 2022 marks the 25-year anniversary of the mobile video game industry. And although some of its greatest milestones have been overlooked by western countries, there’s no doubt about the socio-cultural importance of the medium as an (un)fair legacy of portable consoles and an emissary capable of making people outside the world of video games spend their time popping colored bubbles on the bus.

This industry has seen social phenomena like what happened in the summer of 2016, when people took to the streets to play Pokémon Go and even filled public parks with stampedes of avid trainers. Or the year in which Candy Crush Saga surpassed 325 million active users, including your own parents, who had never even come close to a video game console before. These revolutions don’t measure up to the respect given to an ecosystem that, almost without realizing it, has buried and vilified part of its past, looking straight ahead while plenty of victims are left by the wayside. Due to the advancements in the mobile hardware industry, thousands of video games have become completely inaccessible and without any legal alternative to recover them. And worst of all, mass extinctions are still happening, even nowadays.

Software preservation initiatives are a series of actions, both public and private, that aim to preserve the video game legacy so that future generations can understand and enjoy years-worth of hundreds of games that can no longer be accessed by conventional means. In regard to cell phones, such preservation is much more complicated since there are no physical means of preserving the information nor entities to ensure it. In fact, in many ways, that’s what has happened recently with one of the pioneering game distribution services in the mobile ecosystem.

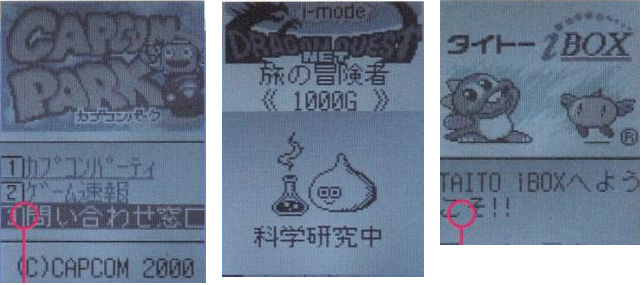

i-mode and the first major extinction of mobile games

In 1999, the Japanese operator NTT DoCoMo fostered the creation of a huge video game ecosystem for mobile devices in which users could download video games from companies such as SEGA, Namco, Taito and Nintendo. While over here, we were playing the snake game, in Asia they had their own Dragon Quest for mobile devices (the archives from back then resemble an archaeological museum). The service has been active for 20 years, offering tons of quality titles based on well-known licenses that did not reach the West in many cases. Meanwhile, their technology has been exported to half the world thanks to the advances in communication protocols of the time that were already within reach to the average user (does anyone out there remember Movistar Emoción?).

The problem arose in November 2021, when the i-mode service that served as a distribution platform for all these games announced its definitive closure. It was at this point that people from the Game Preservation Society tried to download as many titles as possible before the shutdown, as well as buying up old cell phones like crazy to perform an almost blind data dump of as much content as possible before they were no longer accessible. After all these years, licenses have been changing hands, and many of these games could disappear forever from our plane of existence if no action is taken. It’s time to worry about more than just the koalas going extinct.

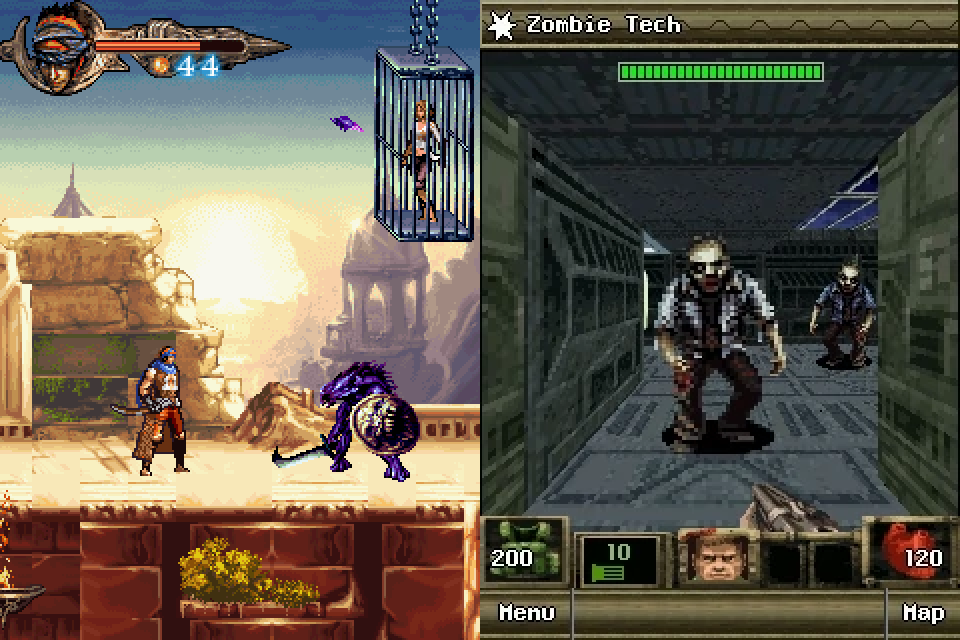

The end of 32-bit architecture app support

But there’s no need to go back to prehistoric times to recall mass extinctions. Without a doubt, the golden age of mobile gaming took place during the rise of the iOS platform as a gaming system. It’s safe to say that the best portable console you could get your hands on back in 2011 was a 3rd generation iPod Touch. Before the Free-to-Play model and other questionable monetization practices were introduced, Apple knew how to lay the quality foundations of a system where, for less than a dollar, you could get games that were easily comparable to the commercial releases from other dedicated platforms.

Once again, the problem came in 2017 when Apple announced they would stop supporting 32-bit apps in iOS 11 which back then, was the latest version of its operating system. The groundwork for this decision was laid out two years earlier when the iPhone 5S came out with a 64-bit processor. In order to get the most out of its architecture, improve security, and free up resources, developers were forced to update their games. The issue was that many titles were no longer supported, and their creators had no intention to adapt them, either due to a lack of interest in their product or a technical impossibility related to the need to redo a large part of their implementation.

As a result, many games were left stranded in limbo (Touch Arcade compiled over a hundred as an example) and can only be enjoyed if you have an old iOS device from back then. Considering the obsolescence of certain components such as the battery and the absence of a robust system emulator to be used by the general public, this means they’re only accessible to speleologists and retro enthusiasts.

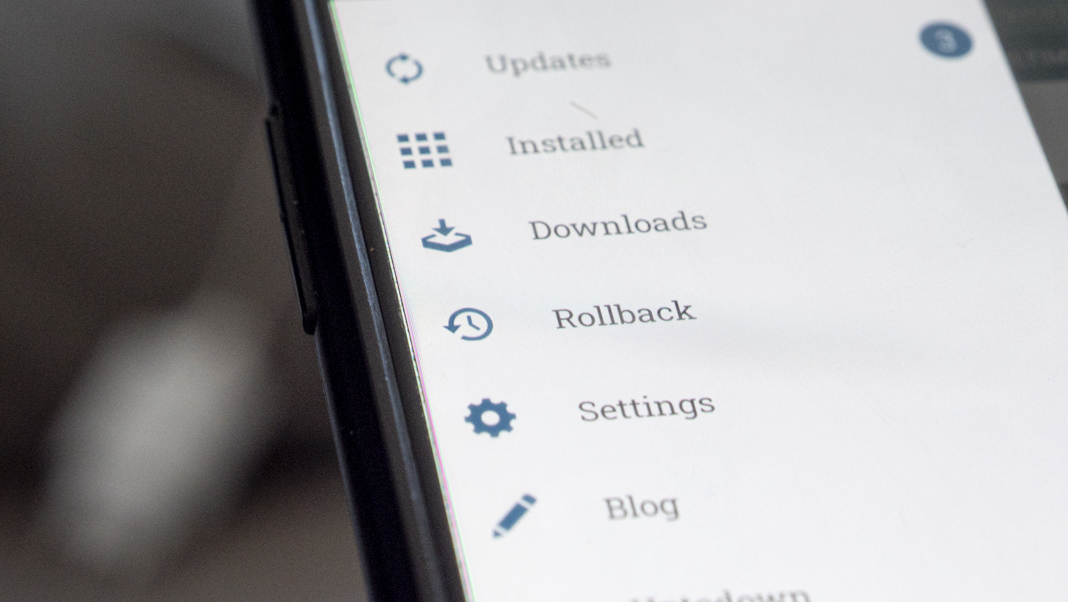

And so, we arrive at the current times, when Google has also decided to do a little spring cleaning. Since August 2021, it’s no longer possible to download apps from Google Play that have not migrated their code to 64-bit. Once again, there has been a sifting of those titles whose developers are no longer active or do not consider them worth the effort. As we announced at the time, Uptodown has continued to support these apps, but there are ever-increasing obstacles when it comes to offering a historical repository that does not discard the past in pursuit of a supposedly better future.

Java games: users to the rescue

Finally, after all this background, we come to the fundamental question: what about software preservation itself? Where can I go to download all these forgotten games? Thinking back to the bustling production of Java mobile games during the 2000s, abandonware enthusiasts have had to come to the rescue after the technology became obsolete.

At Archive.org you can find several GBs worth of handcrafted compilations that act as a sort of Noah’s Ark in order to, similar to what happens with the ‘romsets’ of classic consoles, preserve the legacy when the distributors and rights holders on mobile platforms are not willing to do so. This, together with the proliferation of emulators that speed up its execution on modern architectures, means that you can revisit and save this entire legacy in a safe place. But in the end, these are just hard drives stored in a closet due to a digital Diogenes syndrome. We need to work on a solution the same way that there are public libraries where anyone can read Don Quixote. Well, maybe Cervantes isn’t exactly comparable to Flappy Bird, but you know what I mean.

Uptodown, the first to offer a complete repository

At Uptodown we’ve always believed that keeping mobile apps in our catalog even when they’ve been discontinued is the best way to preserve this legacy —although we respect the authors’ decision when, for whatever reason, they decide to have them removed from our store. Nowadays, half of the users who visit us from mobile devices have an Android version that’s more than 4 years old. What’s more, almost 12% are still using Android Marshmallow, meaning that their devices might even be a decade old —i.e., they might not even support 64-bit architectures. Considering the 130 million unique users we have per month, these figures can’t be ignored. Why should we deny them an app distribution platform that delivers the software they need? This is, of course, a rhetorical question and there are more than a few arguments for it, but even so, we believe users benefit from not being forced to modernize without a compelling reason, especially if there are alternatives to avoid it. In fact, that’s what all this is about: offering alternatives.

This disregard for the obsolescence of digital distribution is the endemic problem of an industry that keeps sending us warnings: in February 2022, Nintendo announced they will stop supporting the Wii U and Nintendo 3DS virtual stores with no intention (at least for now) of creating an alternative distribution channel for titles released on its Virtual Console that will no longer be accessible. This, together with the aggressive company policies regarding the veto of any preservation initiatives, emulation or adaptation for amateur projects means that many works are irretrievably forgotten. Could anyone imagine what would happen if Valve decided to shut down its Steam platform? It would be the end of the world as we know it!

Therefore, we need to keep standing our ground as an alternative app store capable of accommodating all the content generated by an ever-growing mobile industry. Currently, we offer support for older versions of every app, and since our internal cataloging system processes an average of one file every 30 seconds, we already host more than 4 million files. Although these figures continue to grow, they don’t undermine our determination to promote an open, accessible and enduring mobile industry.

So the next time we hear someone saying that “playing mobile games is not really playing video games,” let’s remind them of the 20 years of constant progress, of the millions of players who currently use them as their main electronic entertainment system and of the need to highlight the value of an industry that deserves to be promoted and studied for years to come without having to constantly worry about expiration dates.