We already know that the governments of some historically secretive countries have attempted to preserve the “innocence” of their inhabitants with excessive Internet censorship measures. What in theory should be evolving as the throwing-open of doors in the wake of digital globalization is in fact becoming an absurd crusade whose aim is the absence of information freedom and the elimination of effective ties to the outside world. And here we are not talking about the recurrent offenders, China and North Korea, but rather about Western countries like Spain and the United Kingdom.

Recently, the Spanish Council of Ministers gave free reign to the elaboration of a reform to the 1995 Penal Code, which, among other abusive measures, aims to criminalize the use of social networks to call for protests that criticize state institutions without prior notice to government. In addition, posting images of the actions of antiriot police during a protest is set to become punishable with a fine of not less than €600,000. These are ridiculously disproportionate measures that aim to shield a government that has been besieged in recent years by constant citizen protests against the state’s abusive policies in countless different areas.

A very different but equally reactionary proposition is the one that David Cameron aims to establish in the United Kingdom, which forces all of the country’s Internet service providers to activate by default a filter that blocks access to all sorts of adult content, ranging from esoteric materials to pornography, and including pages that give information on alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, as well as sites that explain how to get around the filters to be installed.

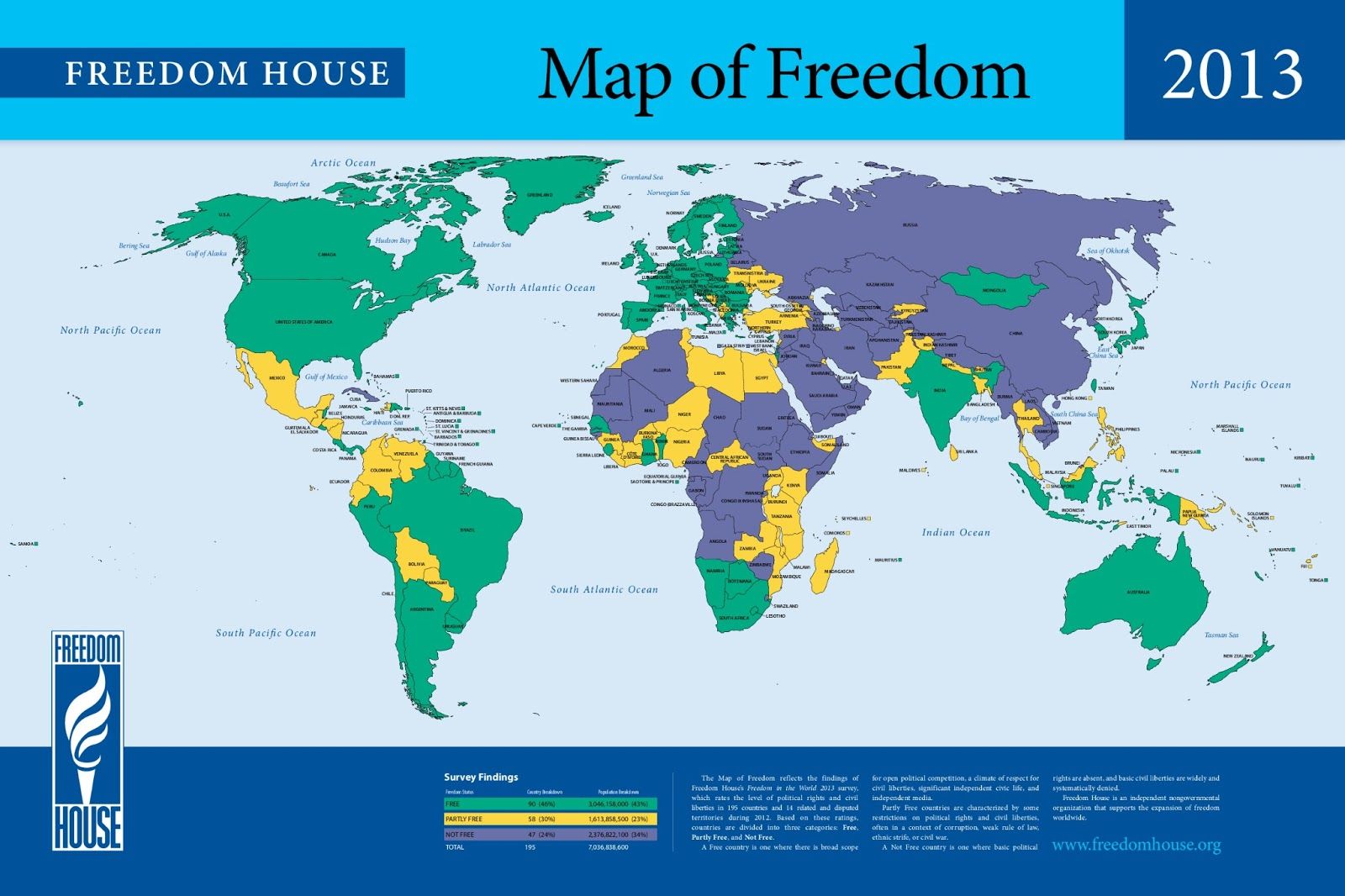

It seems that the top echelons of government are starting to see the writing on the wall. During the so-called Arab Spring that toppled several governments, the Internet played an important role in diffusing information, to the point that the Mubarak government in Egypt totally blocked the Internet in an attempt to stymie the burgeoning revolution. There is another common pattern in the reaction to the growth in web activity in countries undergoing technological development, and that is the fear of a communication system outside the traditional models, which are more easily controlled from the inside. As we all know, people tend to be afraid of what they don’t know, and even more so if they don’t know how to control it.

Let’s turn to the most well-known case outside the West. We already know how things work in North Korea under the Kim clan, with Internet browsing in that country being a bizarre experience in which any trace of outside information is blocked and Internet services are centralized through Kwangmyong, the only service provider, which also happens to be government property. To seal everything off entirely, they even have their own operating system, Red Star OS, based on KDE 3.x.

Most recently, it’s Latin America that’s beginning to suffer movements in this direction, with its governments again worried about the possibility that instant information might provoke the opening of minds among Latin Americans. And again, this process coincides with the considerable growth in Internet access among the population. A recent study on the economy of the Latin American mobile market reveals that there are 164 million mobile broadband users, and predicts a 30% annual growth over the next five years.

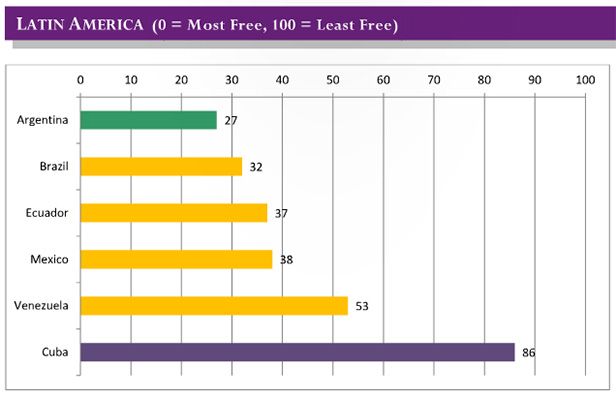

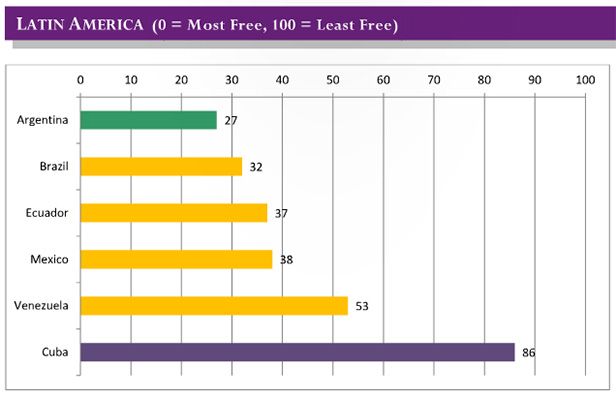

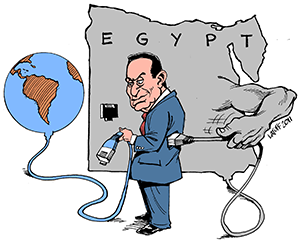

The latest report from Freedom House, which aims to safeguard democracy, political freedom, and human rights, ranks the level of Internet freedom in countries around the world, granting the grade of “partially free” to Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, and Venezuela, with the latter verging on the grade of “Not free.” The recent problems with the trafficking of American dollars as an alternative currency have provoked Conatel, the Internet service regulator in the country, to block all pages that mention the exchange rate, even to the point of asking Twitter to censure those details. Something that, together with the measures already established that limit access to content, put the Bolivarian Republic at the limits of what is “acceptable.” We might as well not even talk about Cuba.

We already know that the road to maturity is difficult, and the fact that the Internet is considered the rock n’ roll of the 21st century means that just like its predecessor, it will be banned and criticized by those crusading leaders who don’t understand it or who see in its reflection a possible social revolution that endangers the hegemony that has been based for so long on disinformation and the bubble effect. This has been happening in Asian countries for many years now, and the same thing is happening in developed countries suffocated by their overly restrictive governments that blame their problems on those that have nothing to do with any of it. It’s also happening in communities beginning to be penetrated by technology at a level never seen before. But, continuing with the analogy, it’s to be expected that popular pressure will put all of them in their place. Or so we hope.